**Spoilers**

As an animation enthusiast, I am admittedly a latecomer in experiencing Hayao Miyazaki’s long-celebrated gallery of animated storytelling. I regrettably had never experienced the spellbinding masterpiece that was Spirited Away when it arrived at Western theatres in 2001. The first time I viewed Howl’s Moving Castle, it was in French and without English subtitles, so I had no real idea as to what was going on. The first Studio Ghibli movie I went to the cinema to see proper was Ponyo back in early 2010. It was a fun, colourful and vibrantly animated viewing experience. However, it felt much too cutesy and saccharine for my liking, as it catered to a much younger audience. Consequently, it lacked the robustness and emotional depth that Miyazaki’s productions were known for. Suffice to say, It wasn’t an ideal first impression of his filmography. After recently viewing his earlier works; Kiki’s Delivery Service, Nausicaa, of the Valley of the Wind and Princess Mononoke I recognised how Miyazaki had become a household name in animated cinema. His library is rich with nuanced fantastical storytelling, strong and compelling character writing, and sumptuously detailed backgrounds and animation.

Synopsis

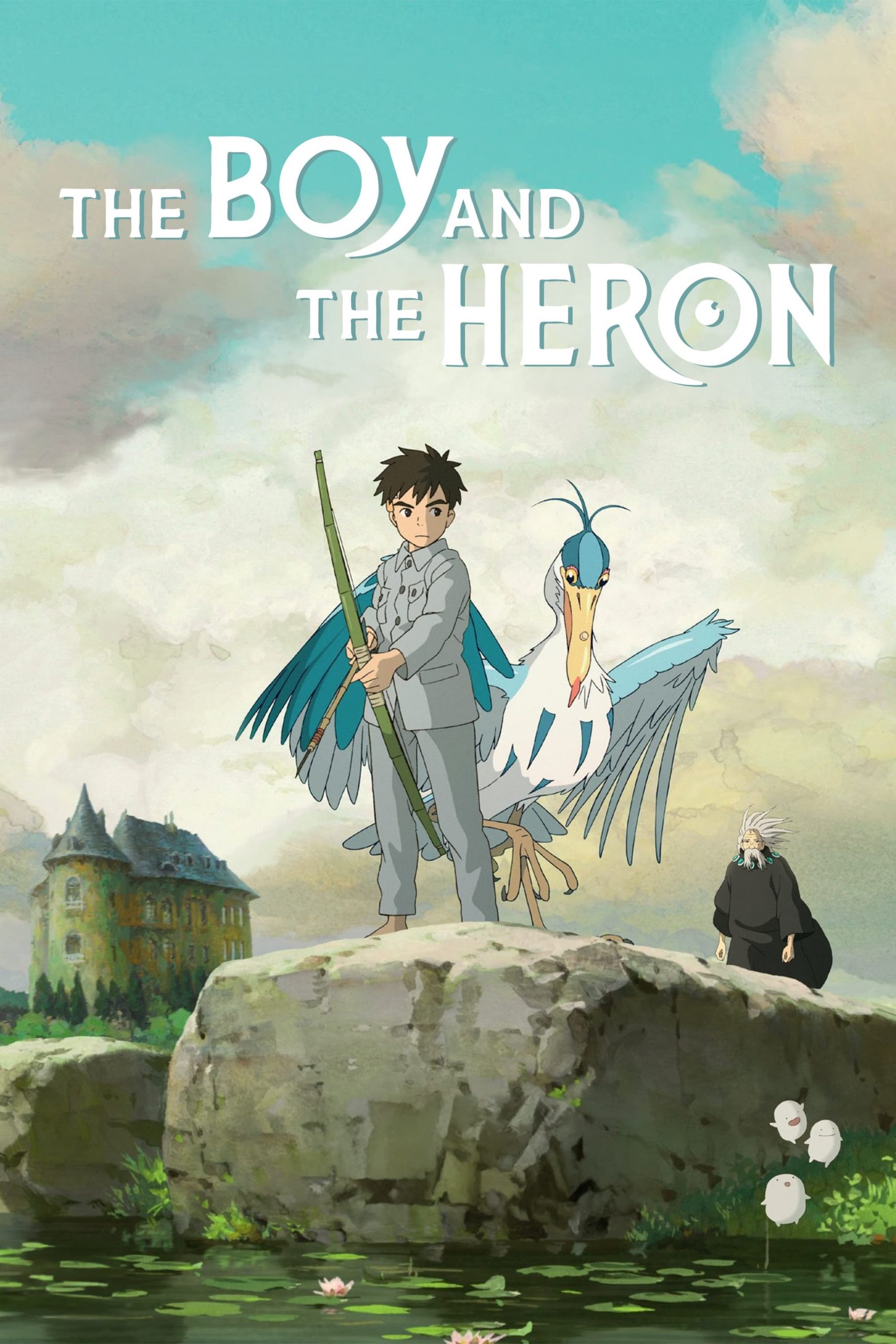

With his latest feature, The Boy and the Heron, Hayao Miyazaki at 83 has many more stories to tell. Adapted from Genzaburō Yoshino’s 1937 novel How Do You Live, the movie tells a tale about 12-year-old Mahito Maki (Luca Padovan). He wrestles with his grief following the death of his mother, Hisako in a hospital fire amid the Asia-Pacific War. His grief, illustrated by a nightmarish opening sequence as he runs through the distorted streets of Tokyo to his mother. Following the family’s evacuation from Tokyo, his father, Shoichi (Christian Bale) re-marries Hisako’s sister, Natsuko (Gemma Chan). They both move into her estate, where Mahito encounters a strange Grey Heron (Robert Pattinson) that pesters him. With the sudden disappearance of Natsuko, the mysterious Heron would guide Mahito down a perilous and personal journey. One of self-discovery through a bizarre world, linked to an old tower in which his Great Granduncle (Mark Hamill) had mysteriously vanished.

Image by Studio Ghibli

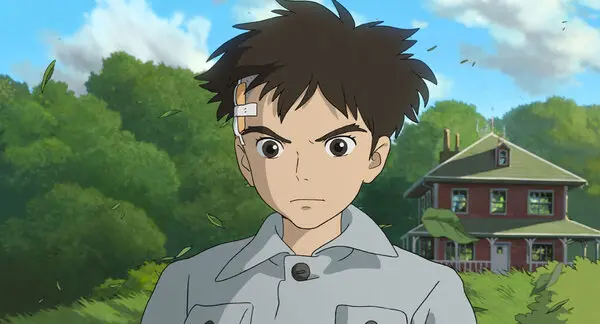

A Troubled Youth

Throughout the movie’s melancholic first third, Mahito is an aloof, and reserved young man with no shortage of emotional baggage. His grief at his mother’s loss and his sudden change of circumstances had made life difficult for him. He would get into a fight during his first day at school and would self-harm by injuring himself with a rock. He initially refused to recognise Natsuko as his new mother, referring to her as “Ms. Natsuko” instead. It didn’t help that his father, a weapons manufacturer, always took a vengeful approach to those who had ‘wronged’ his son. As a father, Shoichi exchanges not a single iota of tenderness, empathy or shared mourning to his son. Echoing the opening, Mahito frequently relives running through streets engulfed in flame with his mother’s voice beckoning him. Furthermore, the use of silent and introspective moments, a recurring staple throughout previous Miyazaki productions provide a poignant reflection of his quiet, internalised trauma.

Image by Studio Ghibli

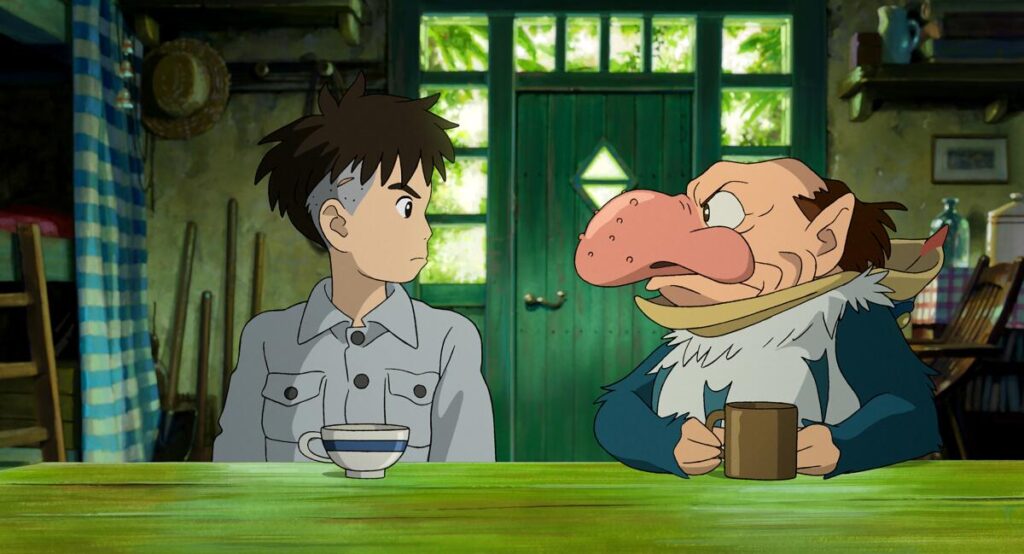

The Moral Ambiguity of the Heron

Miyazaki frequently depicts his antagonists as morally dubious entities. The Heron, for instance flip-flops between a cruel and deceptive trickster, and a comedic spiritual guide for Mahito later on. He initially acts out of malice towards Mahito by luring him towards the tower and baiting him with a double of his mother. The Heron’s true spiritual nature is highlighted as his appearance becomes increasingly grotesque. Additionally, Natsuko is shown to shoo him away from Mahito with a ‘Kabura-ya’, or ‘whistling arrow’. This is traditionally used to ward off evil influences in Shinto cleansing rites. It also implies that Natsuko knows more about the otherworldly nature of the bird than she lets on. It isn’t until Mahito fires an arrow, fletched with the Heron’s own feathers into the top of his beak that he reverts into his true form as a doddery and cantankerous little birdman. A stark contrast to the Heron’s menacing and gangly form. From here on, the birdman would go on to guide and protect Mahito throughout his journey through the strange world he finds himself in after sinking through the floor of the mysterious tower.

Image by Studio Ghibli

The Boy and the Heron, a Dynamic Pair

The contrasting personalities between the sullen Mahito and the goofy Birdman make for a delightfully comedic dynamic. It provides some much-needed levity to contrast with the sombre themes this movie confronts. Moreover, the Birdman, at times brings out a more jocular side to Mahito. A far cry from the antagonism they had previously shown one another. Having seen the movie in English, I was also very impressed with Robert Pattinson’s voiceover debut as the Heron. He convincingly alternates between the personalities of the conniving and treacherous Heron, and the crotchety and comical Birdman, without sounding contrived.

Image by Studio Ghibli

A Cryptic Wonderland

As Mahito wonders this strange new world, it is ambiguous as to what kind of otherworld it might be. I found myself initially assuming that it was some manner of afterlife or underworld. The motif of boats evoked an image of ferrymen, a common cultural symbol of a journey into the afterlife. The sign above the gate to the ancient dolmen reading “All of those who seek my knowledge shall die”, could also be a possible nod to Dante’s “Abandon all hope.” This underworld symbolism is a reflection to Mahito’s struggle in coming to grips with loss, as well as the sign alluding to the world that Mahito may end up losing once he claims the “knowledge” of his great granduncle. But as Mahito, and we, the audience venture further into this world, it conveys a more hopeful theme that where there is loss, there is also new life. The scene with the Warawara spirits demonstrates this theme beautifully. They hover across the night sky like countless stars on their journey to be reborn as people. Even the Pelicans, despite being depicted as predatory entities that attack the Warawara, do so only to ensure their survival. Above all, it highlights the nuanced struggles between life and death that play a major theme throughout this feature. It’s in this moment that we see a more compassionate side to Mahito as buries a dying pelican (Willem Dafoe).

Image by Studio Ghibli

A Metaphorical Journey

The odyssey of The Boy and the Heron is, above all else, a symbolic one. The movie is rich in visual metaphors that provide a dominant narrative vehicle in discussing its various themes. Mahito injuring himself with a rock after a bad day at school, for instance, is an act of both ‘malice’ towards himself and of helplessness in not being able to do more for his mother. The flames appearing in Mahito’s visions of his mother calling to him re-appear as a character motif for Lady Himi, foreshadowing her reveal as his mother at the end of the film. As well, Mahito’s decision to stay in the real world, rejecting his inherited custodianship of the Tower Master’s world is also symbolic. It represents him embracing those that love him in his own world rather than selfishly escaping to another. Overall, the movie’s intricate attention to detail in its metaphorical storytelling is ever-present throughout its run. It even extends to brief instances that could be missed upon initial viewing. One such instance includes the image of a closing lotus flower that appears shortly before the movie’s climax. In various traditions, a blooming lotus represents the overcoming of adversity, and the transcendence of spirit over worldly matter. The closing of the lotus foreshadows Mahito’s rejection of spiritual transcendence and his decision to return to his family. It also represents his resilience and personal growth in the face of both his journey and his inner turmoil.

Image by Studio Ghibli

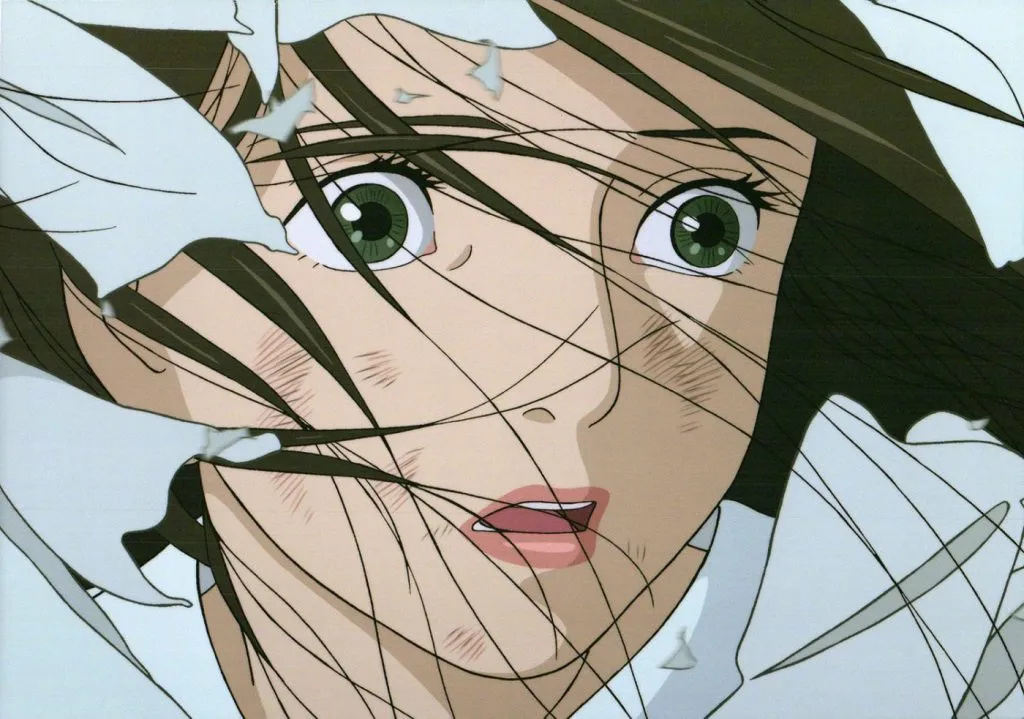

The Shared Turmoil of Grief

Another significant moment rich in visual symbolism is when Mahito re-unites with Natsuko in her delivery room. It’s a quiet and still moment that carries with it a sense of foreboding as paper warding seals hover ominously over Natsuko’s bed. But the moment soon intensifies as Mahito pleads with her to come home with him. The paper seals fluttering and lashing at him like aggressive tendrils mirror Natsuko’s sudden hostility towards him. This outburst can be read as Natsuko wrestling with her own internalized grief towards her sister’s loss, as well as her own anxiety of not being able to care for Mahito in her stead. In the real world, Natsuko masks her inner turmoil and frustration with a kind and nurturing front towards Mahito. Here, however, it manifests as a turbulent storm of paper charms that keep him at bay. It’s in this moment that Mahito calls out to her, acknowledging her as his mother for the first time. A sign that he is willing to let go of his regret and embrace the family that cherishes him. It is a beautiful, intense, and resonant sequence that stands as a testament to Miyazaki’s artistry in communicating his character’s raw emotions through visual motifs and symbols. The moment gives the audience a view into Mahito and Natsuko’s shared pain and helplessness in dealing with their loss, as well as Mahito’s longing for a mother figure and his acceptance of Natsuko as that figure.

Image by Studio Ghibli

A Throwback to Ghibli’s History

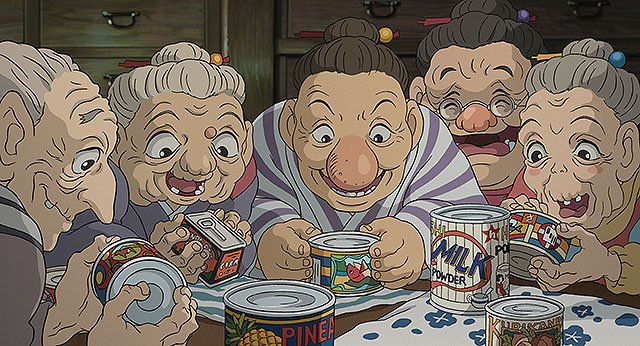

The character designs exhibit an unmistakeable fantastical charm and whimsy that is unique to Miyazaki’s work. Some of these designs pay homage to characters from his previous productions. The grannies in the estate are all delightfully expressive in their demeanour and recall the various denizens in Spirited Away. Likewise, the design of the adorable Warawara spirits evoke the Kodama tree-spirits from Princess Mononoke. Grotesque shapeshifting humanoid creatures have been depicted in prior films like Howl’s Moving Castle and Ponyo. In a similar vein, the Heron gradually shows signs of his humanoid characteristics before fully transforming into his birdman form. There are various other bird characters that range from the colourful yet menacing parrot folk, to the more realistic looking pelicans. At times The Boy and the Heron feels much like a homage to Miyazaki’s previous works through its distinctive character designs alone.

Conclusion

To conclude, The Boy and the Heron is a vibrant tapestry of visual storytelling at its most intricate and dense. At times, this can be detrimental to audiences that are viewing the movie for the first time. I found it difficult to interpret the hidden meaning of moments of dialogue upon an initial viewing. Certain narrative points like how a younger Kiriko and Lady Himi ended up in the Tower Master’s world were left somewhat underexplained. Were they from alternate timelines and had transported there through the tower themselves at some point? It also felt as though the movie suffered from bloat with the details of its symbolic world and narrative. Even with an over-2-hour runtime, it struggled to provide structure to how much of this vast world it wanted to convey. I feel the movie warrants multiple viewings to fully appreciate the scope of the detailed narrative that it weaves. That is not to say the movie was at all a slog to sit through. As with Miyazaki’s previous lineup, The Boy and the Heron was a visually glorious and compelling animated experience. It successfully blends Ghibli’s familiar whimsical charm with poignant and compelling character writing. At times the film felt overly ambitious with the scope of its fantasy world. Nonetheless, the film had effectively absorbed me into the characters’ journey through this dangerous yet wonderous world. If you love the strikingly animated and heartfelt tales within Miyazaki’s filmography, you will likely adore this latest one.